When you next take a sip of your G&T, or hear a certain special-agent say ‘Shaken, not stirred’; think about how it is a wild food that has led to such cultural staples as these.

Juniper (common Juniper: Juniper communis); the key botanical used in gin, is still in the majority of cases harvested from wild populations. With the popularity of gins like The Botanist, other wild botanicals that were once forgotten about have also been given a new lease of life. Our own gin exploration led to the creation of Anty Gin in 2014 produced by Cambridge Distillery and the Nordic Food Lab (see The Telegraph article 'Anyone for ant-flavoured gin?').

In 2008, the Biodiversity Action Plan on Juniper stated that its steep decline in the UK was due to ‘low economic and cultural value’. The Forestry Commission Scotland states: ‘Many juniper populations across Scotland occur in populations of less than 10 plants, with few populations exceeding 1000 bushes: populations should exceed 50 plants to be viable.’ (See here for conditions necessary for maintaining Juniper plantations.) The loss of Juniper bushes could potentially result in the extinction of more than 40 species of insect and fungus which require it to survive. So, let’s take a closer look at ‘economic and cultural value’ shall we…

Mother’s Ruin: Gin and Wild Juniper

Going back to the 17th-century Juniper was one of Scotland’s most important exports; predominantly being sold to Holland and Belgium for the production of genever; an early type of gin (which they still produce today). At the start of the 20th-century, the production of gin really began to take off in Scotland with the ‘golden age of gin’ and thus we started to keep the Juniper harvested from the high and dry parts of the Highlands to ourselves. Today around 70% of gin produced on our island comes from Scotland. Juniper is the essential ingredient in order to call something‘gin’ – giving the drink its fragrant pine, turpentine, slightly peppery flavour – and is thus in high demand from the gin industry. 'The variety of flavours you can distil down from the British landscape is quite extraordinary,' says Tim Cain, distiller at Persie Gin, 'But it all comes back to Juniper, it is gin after all'.

Last Orders?

Today wild Juniper berries for the UK gin industry largely come from the Mediterranean; countries like Italy and Macedonia providing a large percentage of the imports. Juniper berries from these countries’ warm climates result in berries which have a desirably high oil content which imparts the distinctive flavour of gin. However, there are other issues as to why we look overseas for wild Juniper. The most important being that our wild Juniper in the UK has been declining for a long time.

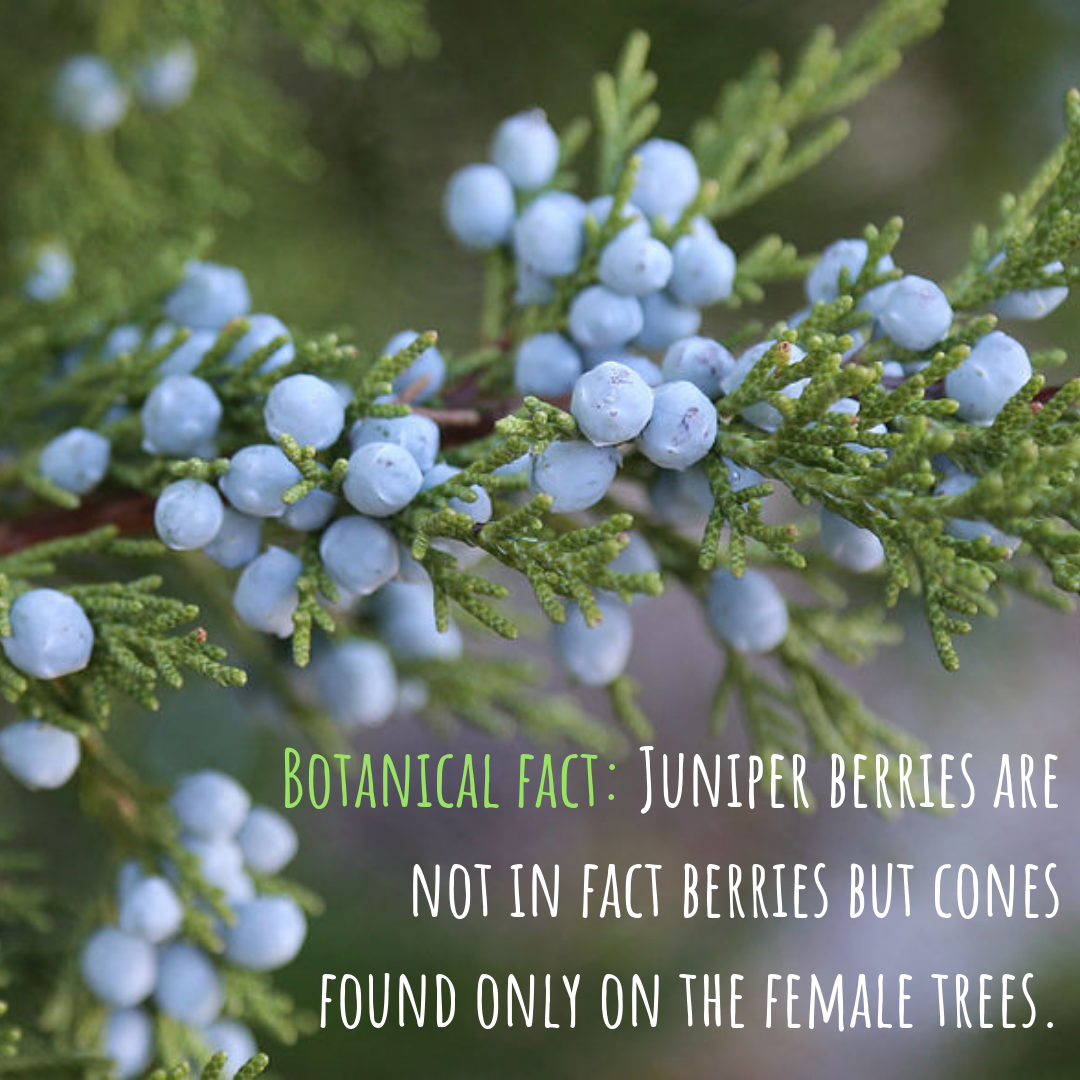

The reasons for this are manifold; the plants being dioecious (having separate male and female plants) means that isolated populations can find wind-borne pollination difficult. The plant has also experienced widespread die-back as a result of the fungus-like disease Phytophthora austrocedri. As a result, they were the first species to be fully collected in Kew’s Royal Botanic Gardens tree seed project which began in 2013, thereby securing its future survival.

One of the biggest factors in wild Juniper’s decline has been its difficulty regenerating itself. Despite its ability to grow in a wide range of soil types; it requires something of a ‘sweet-spot’ of grazing in order to flourish. Too much and the younger seedlings are prevented from developing; too little and the resulting tree cover doesn’t allow growth. Add to this that around 70% of Juniper plants are too old to produce a sufficient number of seeds.

The comeback

So, is there good news? Well, the machinations of our capitalist system have revalued wild native Juniper. We are experiencing a gin craze; the drink overtook the sales of whisky in 2015 for the first time in the UK and the number of small distilleries is increasing year-on-year. ‘There is a need to promote a greater plant supply from sources across the range of juniper in Scotland to meet increasing demand,' says the Forestry Commission.

And so, a number of distillers have begun working with conservation groups to slowly initiate sustainable, commercial foraging of wild Juniper on our island again. There are currently four gins which use 100% Scottish Juniper (Crossbill Gin, Inshriach Gin, Loch Ness Gin and Badvo Gin). Crossbill gin is named after the native bird found only in the pine forests of Scotland, if that wasn’t Scottish enough; in the winter when the still got too cold for the vapours to rise it was adorned with a tweed jacket to keep it warm.

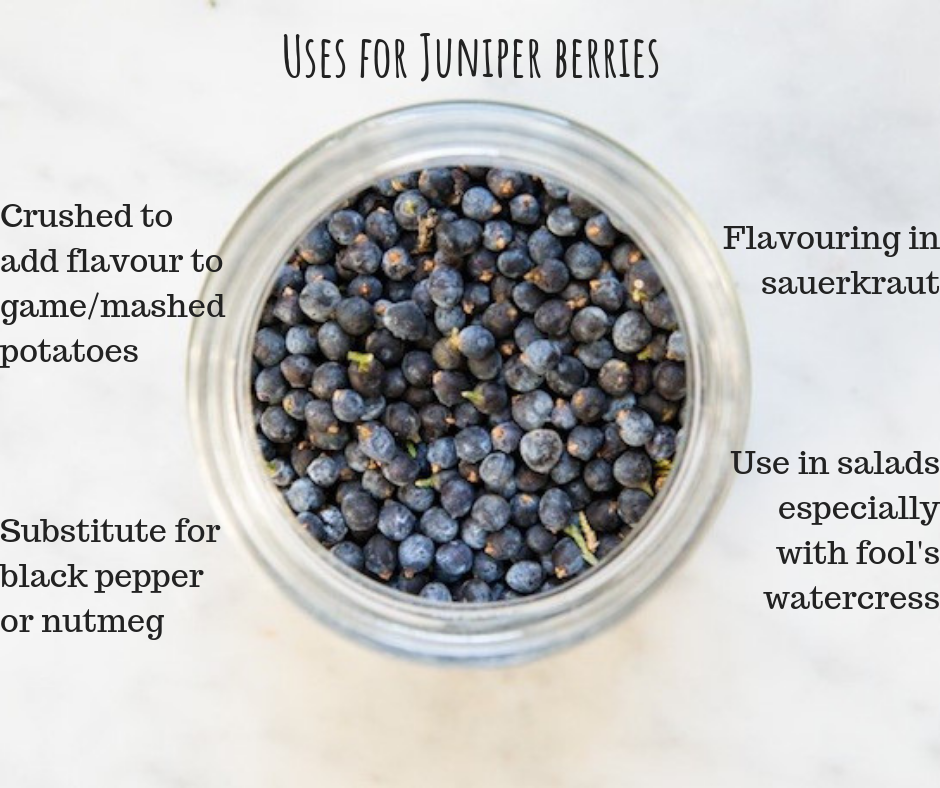

There are benefits other than provenance to using locally-sourced juniper berries; for one, it can be ensured that sustainable foraging practices are adhered to. In addition, when using the more aromatic fresh berries as opposed to dried (as is more common) only 1/5 of the quantity of berries need be used.

A wild Juniper plantation has been planted in Scotland; the first for decades. It will be a slow process; the growth rates of Juniper necessitate that; even in ideal conditions after a few years it might only grow to around 30cm and it takes 2-3 years for berries to ripen. But whilst sustainably harvesting this berry from our lands could be seen as a novelty to some; for others it presents a model for the future. One where we rely on wild plants to provide us with a resource - year-on-year - thereby meaning we value not only its survival but its longevity too.