August brings a shift for our wild edibles - driving us out of the fields and towards the water. However, back in the fields there are a few unexplored resources.

The first one you can see - wild grains: if you scan across a field of wild grasses with a hungry and enterprising eye then what you see is usually smaller (and more nutritionally dense) wild versions of our cultivated grains. There are technical problems to overcome before we can really begin to make good use of these wild grains but we have it in our sights and some of you who have come to visit us at Forager HQ have had the opportunity to work with some of our initial harvests.

The second untapped resource you can hear before you see - grasshoppers and crickets! It's one of those background noises which can easily be tuned in and out of your immediate attention but lately I've been finding it almost deafening. It's been bugging me - hundreds upon hundreds of little protein packets announcing their presence. Entomophagy (the fancy word for eating bugs) is nothing new but it has gained an increasing amount of attention in the Western world - back in 2013 the FAO (Food & Agriculture Organisation - a branch of the UN) published a 200 page document titled 'Edible Insects' which gives a thorough and detailed exploration of the potential benefits of including insects in our diets. Last year saw the opening of the UK's first edible insect restaurant The Grub Kitchen in Pembrokeshire which is sited on and forms part of the research at The Bug Farm. You can even buy bug bars from UK company Grub.

If you still find the thought of eating insects unbearable then it's worth taking note of the following in this excellent article from IFLScience:

'you might be surprised to find out that you already regularly eat them. If you check out the FDA’s Defect Levels Handbook, you can see just how many buggies you could be eating on an everyday basis. Take beer for example—the acceptable limit of insect infestation in hops is 2,500 aphids per 10 grams. Canned fruit juices are allowed up to 1 maggot per 250 ml, curry powder is allowed up to 100 insect fragments (head, body, legs) per 25 grams and chopped dates are allowed up to 10 whole dead insects. The list goes on and on. Is this churning your stomach? It shouldn’t, because you’ve been eating them for years and it hasn’t bothered you.'

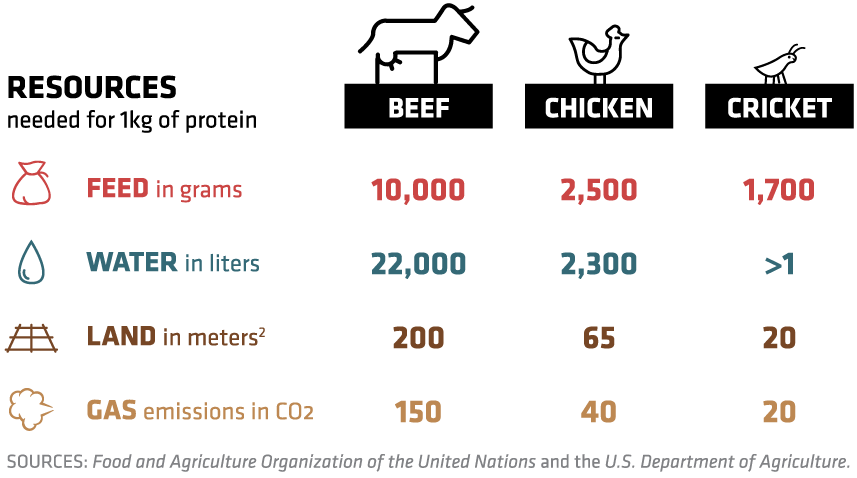

One of the main points cited in favour of eating insects has been their capacity to convert protein at a much higher rate than our current livestock. Looked at from a reductionist point of view a cow can be seen as a tool to convert grass (which is not all that digestible to us) into the more easily digested form of meat. Grasshoppers, crickets and other bugs can be viewed in much the same way as ways to turn matter which is not digestible for a human into tasty edible foodstuffs - the difference is that they are claimed to be far more efficient at making that conversion with it taking 8 times as much feed to produce the same amount of edible meat from cattle as from crickets. With a growing global population that's a pretty compelling reason to join the 2 billion people who already regularly consume insects as part of their diet.

However, there has been some research which points to the opposite being true. In this article in Time magazine a study is looked at in which crickets were fed on a variety of different feeds and the protein conversion was only marginally better than that of chickens. On the face of it that might persuade some people that entomophagy is not a viable addition to the current food system which is also what is being discovered on a farm in the Netherlands raising bugs and finding that they are having to price them more like caviar to remain in business. Nevertheless, the point which seems to be missed from all of these is that those experiments are trying to take something out from it's place in a natural system and still try to maintain a high level of efficiency. If you happen upon a bug and eat it then as with all wild food your total inputs into that system are basically zero whereas if you take it out of the wild and create a system where you are having to supply it with food (which we have to grow) and shelter then you remove all of the efficiency provided by a zero input system.

Over the next few weeks while the fields are buzzing with life we'll have the chance to put my theory to the test as we begin harvesting Wild Grasshoppers and Wild Crickets for anyone who is willing to jump in and try them. Over the past few years we have been able to gradually refine our Wood Ant harvest so that we have now found an efficient way to do it and we anticipate that we'll be doing the same with our harvesting methods for these members of the Orthoptera.